Goodness - in any country

Michael Redhill's play Goodness is partly inspired by the genocide in Rwanda, as the program notes explain. Yet the veteran Toronto playwright has chosen to craft a script where the conversations about goodness, war, ethics and revenge, could apply to any of the genocides that have happened in the last century.

A version of Redhill's self, a Michael played by Gord Rand, goes to Poland in search of those who might remember what times were like when his Jewish forbears were murdered in a town square. He's mocked - it was your tragedy? you weren't even alive! - and finds that no one wants to speak about times past.

When Michael returns to London for a flight back to Canada, he's stuck in that city for seven hours. An old man in a bar asks what he's been up to, which launches further mockery - your histories don't intersect with those in Poland, yours is a subplot of theirs! - until the gent becomes serious. Turns out he thinks Michael is someone who still believes people are capable of goodness. Turns out this old man has been sitting in the bar on a regular basis trying to work up the nerve to go ring the buzzer at an apartment across the street.

Turns out that Michael, compelled by the old man's cryptic instruction that he should go and say the name "Mathias Todd" to find out all he ever wanted to know about his question, does go across the street to say the magic words. As if they were a spell. As if a story could be unlocked.

A story is indeed unlocked, and it's powerful because good and evil are not clearly set apart. An old woman, suspicious at first, decides to tell Michael her story and he's not allowed to go even when he's had enough.

Althea, who has watched her people be killed in a genocide, ends up as prison guard to Mathias, the man accused of inciting the hatred and murder that devastated the country. He may or may not have Alzheimer's, the prison guard can't decide. If he does, then a huge part of revenge becomes dismantled because Mathias would not experience the moment of understanding that violence against him was a form of retaliation.

As Althea tells her story, Michael interrupts. Scenes blend between past and present seamlessly as if the storyteller is replaying moments in his head, trying to make sense of it all. Characters from the past argue with those in the present, testing hypotheses of "what if?" Gradually Michael, and we, realize there are many things that can't be undone, it has to be accepted that terrible things did happen, that that is the way things were.

Redhill is digging for answers to a question that underlies all these other ones. His characters ask repeatedly: why do good people do bad things, and what becomes of them after they do?

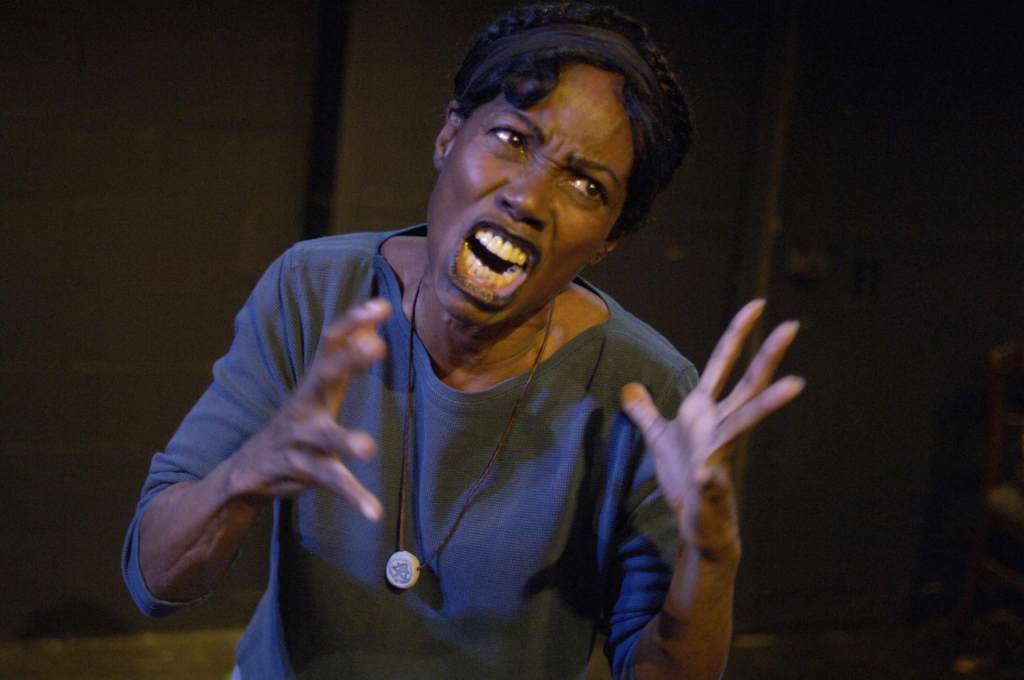

It may sound pat and polished when compressed into a phrase like that, but Goodness is anything but smug or tidy. Michael is likeable though a bit naïve, thinking that his divorce isn't his fault. Althea (played by Lili Francks when old and Tara Hughes when young) is hard on him and on everyone else. She's bitter, but she did a good thing. Or did she? She accuses Michael at one point: "You think that because someone is capable of suffering, they must be good." Thus the inverse question also appears:if someone is not good, what does it mean when they do a good thing? And, is the price of doing a good thing to live in a hell forever after that act?

Althea's bitterness, and her insistence on living in a dark, curtained apartment, reminded me of a horrific image that from a new film called Triage: Dr. James Orbinski's Humanitarian Dilemma. In the film, Dr. Orbinski, who surgically handled terrible wounds that resulted from the genocide in Rwanda, revisits the country where he worked as Head of Mission for Doctors Without Borders in 1994.

In one scene, a man with a deep bullet-wound scar in his head takes Orbinski and his translators across a desolate field, narrating how hundreds of people were herded onto the grass and shot, falling on top of each other. He leads Orbinski to a small wooden building that apparently gives off a particular stench. Inside: bodies. Lime-covered bodies. The man has been patiently, absurdly, digging up the corpses and preserving them with lime so that he will not forget - and he's been doing this for twelve years.

The man lives in a hell that someone else forced on him, but he remains there actively. Does he have a choice? Orbinski doesn't go into the question, but the image led me to wonder if it's possible to heal from trauma, whether personal or national, without letting go of the past.

Back to the stage in front of me, though. All the acting, singing and writing in Goodness is absolutely professional and leaves the audience breathless. Mental habits are broken soundlessly, gently: the Holocaust is taken off its pedestal as being "the" genocide; and the desire to point at any specific event in history as the "logical" reason for why this or that conflict occurred is confounded because we don't know what country or year the play exists within. So we're able to look at the broader, underlying ethics that range between peace and hatred.

This insight blazes on the stage in a simple, provocative moment. Michael describes meeting the old woman and looking at her pale skin and into her pale blue eyes: but as he says this, he's staring into the jet-black eyes of dark-skinned Lili Francks. All races and countries where genocide has occured fuse into that moment.

Redhill seems to believe that the basic human morality is one of goodness, despite the hatred that his characters have seen thriving. Dr. Orbinski's film emphasizes that too. If the baseline of humanity is goodness, it's an extremely acute, and generous, mind that can look so directly at hatefulness without being poisoned and making a continuous hell to sleep in for the rest of its waking days.

_A Magnetic North production, Goodness is performed byLayne Coleman, Lili Francks, Tara Hughes, Ross Manson, Gord Rand and AmyRutherford. Direction: Ross Manson; Music coach: Waleed Abdulhamid; Stagemanager: Maria Costa; Sound designer: John Gzowski; Music director: BrennaMacCrimmon; Music coach: Teddy Masaku; Lighting designer: Rebecca Picherack;Set/costume designer: Teresa Przybyiski; Music coach/ Assistant director(Vancouver tour): Sarah Sanford_