Luminato 2010

Sorry Montreal, but the title bearer of Canada’s “City of Festivals” is no longer so clear cut or in your corner. Luminato, the festival of arts and creativity, has done a lot over the last four years to spearhead a veritable boom of cultural events that pack Toronto’s summer months - including an ever growing Ontario version of your own piece-de-resistance, Just For Laughs.

Friendly rivalries aside, Luminato is indeed a leader of Toronto’s cultural festivals in two respects; first, chronologically as the first major festival of the summer - a kind of grand kick-off to the season as a whole - and second, in terms of scope, scale, and spectacle. Thanks to some major government funding and an unavoidably opaque element of corporate sponsorship (some of the most visible outdoor installations were giant L’Oreal tents), Luminato possesses a rare ability to mount large scale and high-profile performing arts works originating from both inside and outside our national borders.

Luminato is comprised of events that fall into nearly every cultural category, from cuisine to couture, literature to music, visual art to poetry, and of course plenty of theatre too. Each year Luminato sets a theme, or multiple themes to tie many of its curated works together. One can certainly strain to make the intellectual connections if one so desires, but it is more satisfying an experience to simply take in what the festival has to offer and find meaning after the fact. In my case, I found myself confronted by a number of works which upon reflection I realized were all based on real lives, real events, or real situations. Of course one might not think this to be particularly remarkable given that a great deal of contemporary theatre is inspired by reality and not only the playwright’s imagination, but what did stay with me was the very un-documentary style many with which many of these pieces were presented, despite a more straightforward treatment and traditional narrative being the more obvious choice.

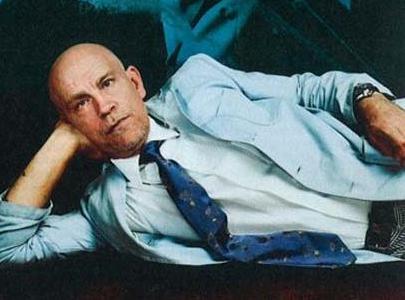

Certainly the most attention grabbing piece of the festival (at least next to Rufus Wainright’s Prima Donna) was The Infernal Comedy. No doubt much of its hoopla could be attributed to the celebrity power brought to the piece by quirky star John Malkovich, but that would be an over simplified explanation of the buzz that surrounded it. The fact that the subject of the piece is now-deceased Austrian serial killer Jack Unterweger, and that the bizarrely minimalist theatrical proceedings are backed by two sopranos and a period orchestra is without question the other major draw.

Malkovich has a presence that can only be fully appreciated in person. It is certainly easy to chide his characteristic inflection and lilt when watching him on screen, but they have an entirely different effect when experienced in the flesh. His attempt at an Austrian accent may have been an abject failure, but it was easy to forgive him given the eerie ease with which he inhabits the persona of a charming yet transparently unstable murderer.

To portray any real-life figure of infamy almost always invites accusations of a sympathetic treatment of the subject or in cases such as a serial killer, exploitation of the victims. Fortunately Malkovich and the rest of the creative team deliver Unterweger in a surreal enough manner (as though he is reluctantly hosting his own book signing while drifting in and out of social composure) that the emotional experience for the audience is sufficiently distant. Having said that, there is something equally disturbing and captivating about watching the iconic actor physically distract, manipulate, and occasionally assault his elegantly dressed soprano counterparts - memorably kicking at their skirts mid-aria, and later strangling them with lingerie.

Also touching a nerve was Volcano Theatre’s Africa Trilogy. As the name suggests, the evening was a trio of individual pieces, each written by a different playwright of a different nationality, and each examining some of the lesser examined facets of the still enigmatic continent.

A piece about an emotionally strained WASP couple returning from a multi-year humanitarian trip provided an insightful look at what happens when the western perception of Africa and its realities intersect, while a piece about a Kenyan author who escapes the slums via the success of her memoirs and her participation in a development conference was an artful reminder of the developed world’s tendency to make patronizing assumptions about Africa and it’s inhabitants. The most revealing piece of the three was perhaps not the most artistically strong, but did make a lasting impression thanks to its fascinating commentary on free-market capitalism. Presenting Nigeria as a playground in which said system has been left to fester without regulation (or rather institutionalized de-regulation as mandated by western bodies such as the World Bank and IMF), the piece offered the examples of the privatized fee-based education for even the poorest children, the citizen-unfriendly and economically one-sided oil industry, and the rampant and corrupt email scam industry (think of the famed Nigerian Princes), arguing that all are corrosive forces and the result of greed run amok and without limit.

Finally, Homage from 2b Theatre Company was not the most grand or talked about work of the festival, but was likely one of the strongest. Set in the Canadian Opera Company’s spacious rehearsal hall, this piece about the real life story of artist Haydn Davies and the destruction of his landmark sculpture at the hands of short sighted politicians was by no means the type of “preaching to the choir” types of art-themed stories, nor was it an overly pretentious treatise on the meaning of art. Although certainly containing and subtly communicating a number of grand ideas, ‘Homage’ is rather a human story with grand ideas backing it up. Philosophical contemplation on the part of the audience is invited, rather than imposed, in part thanks to a flowing script, impressive circular staging, elegant direction, atmospheric lighting, and a remarkable performance from Toronto gem, Jerry Fraken as Davies. With profound questions asked such as ‘is art owned by the artist or the purchaser’ and ‘what is the relevance of context to art’, it is impressive that ‘Homage’ never veers into the annoyingly abstract or effete.

Although Luminato may be the victim of its own success in that an excellent year may seem tarnished in comparison to a previous stellar year (and most so far have been stellar), there is no disputing its once sudden and now very established importance. As Toronto, like many North American cities turn away from manufacturing and other fading 20th century industries, and look instead to intellectual and cultural sectors to pave the way for future growth, landmark festivals such as Luminato don’t seem so much like quaint recreation as they do beacons of confidence.